Hello!

You’ve received this email because you’ve signed up for noodsletter. Thank you.

If any of you want to send over things you find interesting, or that you think I would find interesting, I encourage you to do so! (Thank you to all who do!)

A couple recipe-like things today, and not much else. I am in the final throes of editing for my cookbook manuscript, after which…I’m done with the writing bit, at least. (Still got photos to figure out.) I’ll do a jumbo link noodsletter next time, for those of you who like clicking on things.

Remember, all the recipes ever published in noodsletter have been archived in the very first noodsletter, which you can find here.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Book Bit

Good. Now I can begin to suck. Watch me closely. I take a stone from the right pocket of my greatcoat , suck it, stop sucking it, put it in the left pocket of my greatcoat, the one empty (of stones). I take a second stone from the right pocket of my greatcoat, suck it put it in the left pocket of my greatcoat. And so on until the right pocket of my greatcoat is empty (apart from its usual and casual contents) and the six stones I have just sucked, one after the other, are all in the left pocket of my greatcoat. Pausing then, and concentrating, so as not to make a balls of it, I transfer to the right pocket of my greatcoat, in which there are no stones left, the five stones in the right pocket of my trousers, which I replace by the five stones in the left pocket of my trousers, which I replace by the six stones in the left pocket of my greatcoat. At this stage then the left pocket of my greatcoat is again empty of stones, while the right pocket of my greatcoat is again supplied, and in the right way, that is to say with other stones than those I have just sucked. These other stones I then begin to suck, one after the other, and to transfer as I go along to the left pocket of my greatcoat, being absolutely certain, as far as one can be in an affair of this kind, that I am not sucking the same stones as a moment before, but others. And when the right pocket of my greatcoat is again empty (of stones), and the five I have just sucked are all without exception in the left pocket of my greatcoat, then I proceed to the same redistribution as a moment before, or a similar redistribution, that is to say I transfer to the right pocket of my greatcoat, now again available, the five stones in the right pocket of my trousers, which I replace by the six stones in the left pocket of my trousers, which I replace by the five stones in the left pocket of my greatcoat. And there I am ready to begin again. Do I have to go on?

From Molloy by Samuel Beckett.

I was reminded of this passage (it’s far longer than what I’ve excerpted) because of this story about stir-fried stones.

ThE bEsT gRiLlEd ChIcKeN

I like to think I’m not one of those hyperbolic people yammering on and on about the best this and the best that (at least not in writing…in public), but I believe this is actually the best way to prepare chicken for the grill1. It requires just three ingredients, two if you skip the sake, which you can do and it’ll still be amazing. All the flavor is coming from the chicken (and charcoal, if your grill uses charcoal).

There are a couple of caveats:

-This is only about wings.

-Not just only about wings; only about the part of the wings known as the “flat.”

-You don’t have to grill them; a broiler works just fine.

-They’re better when skewered.

-They’re much better when you use a good chicken. If you’re skeptical, try it with a bad bird; it’s delicious enough that you’ll be curious about how much better a better bird could be.

Ok! Let’s get to chickenwinging.

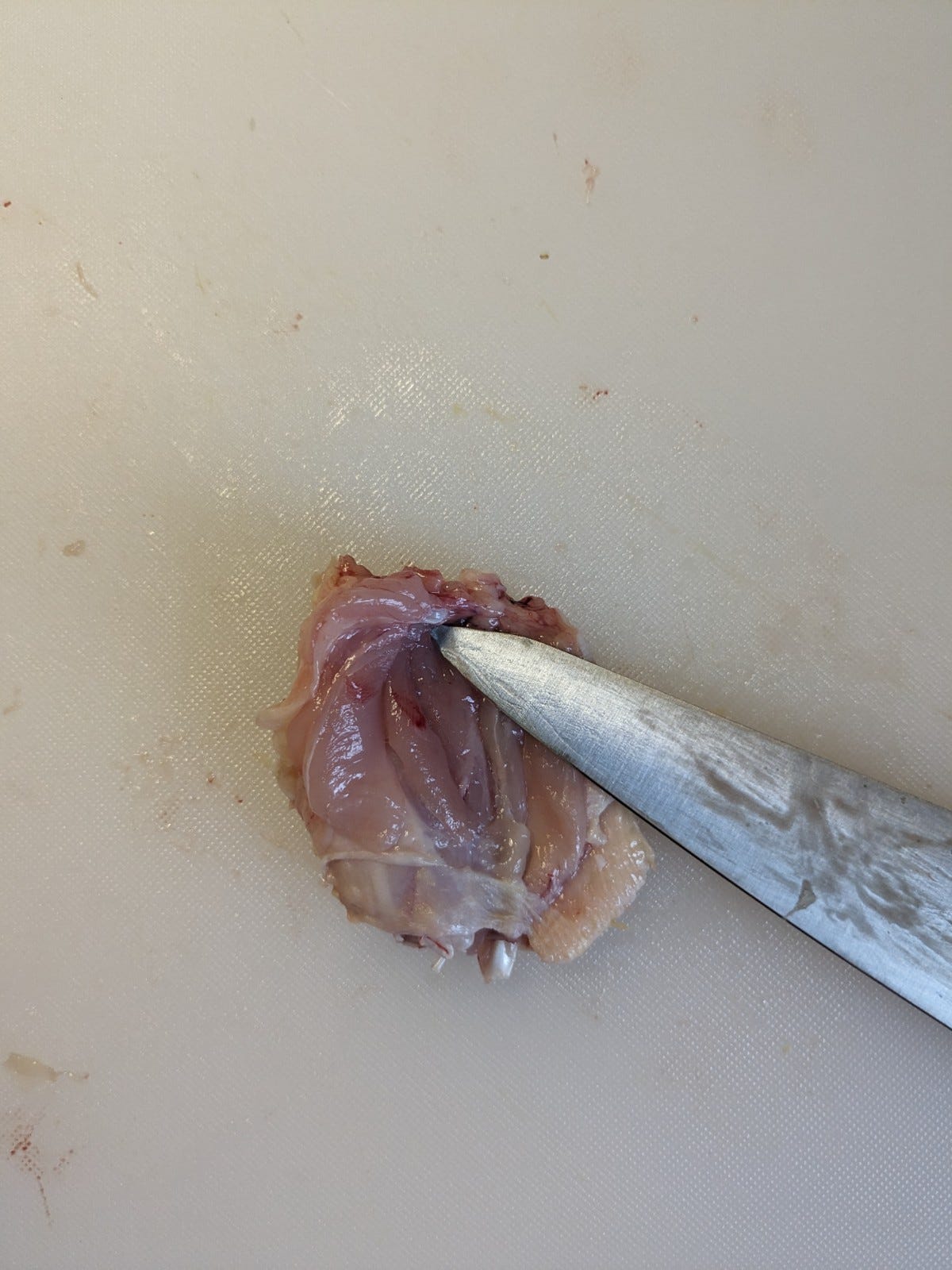

This is more or less how lots of yakitori shops prepare the chicken wing flat. A yakitori shop probably does it neater, and while there’s a lot of different ways to futz with the technique, they are probably doing it in basically the same way. The best way to do this is to just show you pictures, starting with a whole wing. (If you’re wondering how I took these pictures with just my two hands without getting my phone all gooped up with chicken juices, you’ll just have to keep wondering: many are my talents, many of them mysteries.)

This is nearly impossible to do with a dull knife. More specifically, a dull knife tip; all of the cutting is being done by the top 1/2 inch of the blade2.

If this looks a little messy to you, or you want those bits of cartilage on the edges out of the picture (why? they are delicious!), you can square off the ends of the flat before butterflying it. (Going to include the rest of the photos, too; this is with the other wing on the bird, and it might be useful to you since everything is flipped.)

Now that you see it, it sort of makes sense, right? All the skin is on one side, in a single, flat plane. The “flat” has transformed from kind of elongated ovoid shape into a truly flat piece of meat: Skin, fat, meat, then bone.

When you cook these over (or under) direct heat, with the skin side facing the source of heat, the skin gets kind of crispy, but not crispy like it would be coming out of a deep fryer. It’s actually a little soft, but “crispy” along the very outer edges, as the fat underneath the skin doesn’t completely render out. The meat itself is inevitably “overdone”—cooked to in excess of 165 degrees F—but, since it’s dark meat, that doesn’t really matter; doubly so because it’s attached to hot, not quite rendered chicken fat, so even if it’s dry, it eats plenty juicy.

That’s not to say you can’t get the skin crispy; you can. It’s to say that crispy skin is not the point; you want delicious, unctuous, slightly “crispy,” slightly charred skin with a layer of not-totally-rendered fat underneath it. Since crispiness isn’t even the goal, dipping the chicken flats in sake right before salting them (very generously) and throwing them on the grill makes sense: the sake slows down the rate at which they char and the fat renders out, because the water has to boil off first; when the water in the sake boils off, it leaves behind some of the savory umami notes inherent in sake, thanks to the koji mold used in its production. The result is a very, very tasty piece of chicken that, if you salted it sufficiently, should be the best piece of chicken you’ve ever eaten. Give it a squeeze of lemon, a little tap of shichimi togarashi, if you want, but not after you try it straight up.

It helps to skewer the flat, which can be a little tricky. I didn’t take snaps of that process because frankly it’s impossible to do as one man with two hands. But here’s a cooked photo of a wing I did on my little electric grill a while back. The idea is to streeeeeetch the skin as far as it can go; by doing so, more fat will render out of the skin, which in turn will make it crispier (this is just because of the larger surface area being exposed to more heat; unskewered, the skin will want to contract).

Can you do it with the drumette? Sure. You can butterfly a drumette so all the skin is on one side, and you can grill it in exactly the same way: dip it in sake, salt it generously, cook it 95% of the way through on the skin side, then kiss it on the meat side and eat it. It’ll be great! But drumettes don’t have the same layer of fat as the flat; they also are largely white meat, so they’re necessarily going to be dry. The drumette simply doesn’t deserve a superlative, in any context.

To recap the process:

Butterfly the flats (as many as you like).

Skewer them, one per skewer (optional).

Dip them in sake (optional).

Salt them generously, on both sides.

Cook them over (or under) direct heat, skin-side facing the source of heat until the skin is a little crispy and a little charred, and the meat side is white and no longer looks raw.

Turn them over and give the meat side a 30 second kiss of heat.

Serve. (Take a big whiff of the chicken before you start eating, it’s intoxicating.) A squeeze of lemon is great, so is a little shichimi togarashi.

Please make this. If you’re near a grill this weekend, the weekend in which every American is commanded by the constitution and the courts to be within 5 feet of a grill for at least an hour, you HAVE TO make this. Please use a sharp knife; please be very careful…it’s very easy to cut yourself when working with wee flats and drumettes (if your chicken is very wet—and some of them are because of our cursed animal husbandry system—dry them thoroughly with paper towels, then butcher them on top of a dry paper towel).

But, really: best chicken you’ve ever had IN YOUR LIFE (if cooked over charcoal). Until the next time you make ‘em, with progressively better-quality chickens.

Miso Kohlrabi, Babi!

We had a hefty kohlrabi from the farmer’s market in the crisper drawer and we needed some kind of vegetable for dinner the other night, so I used a variation on the proto-recipe for the miso dressing in the last noodsletter. It was very good. I present it here as the first in what I hope will be a persuasive series on eating kohlrabi; it’s good stuff. (I sort of first threatened this series in noodsletter 5 while talking about a celeriac slaw.)

I used a slightly different ingredients:

2 teaspoons miso

2 teaspoons sherry vinegar

2 teaspoons sesame oil

Just mixed up until thoroughly combined, and then tossed with matchsticks of kohlrabi.

Kohlrabi, for those who don’t know, is just a varietal of broccoli that has been bred for its stalk; the bulb is just a big broccoli stem, basically, but much sweeter and less crunchy. This is another instance where a mandoline is very useful—and of course, a cut-proof glove. Although kohlrabi is relatively soft, once you peel the fibrous skin; it’s more like cutting a potato than it is a carrot.

The second best is kanat, the skewered grilled chicken wing flats available in seemingly every grill restaurant in Turkey. Sasha published a great recipe for them over at SE.

This my Fujiwara honesuki. Check out my non-knife guy knife guy collection.