Hello!

You’ve received this email because you’ve signed up for noodsletter. Thank you.

If any of you want to send over things you find interesting, or that you think I would find interesting, I encourage you to do so! (Thank you to all who do!)

As I wrote last installment, changing things up for a couple weeks.

All the recipes ever published in noodsletter have been archived in the very first noodsletter, which you can find here.

Pre-order my cookbook, Homemade Ramen, now!

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Book Bit

The service of philosophy, of speculative culture, towards the human spirit, is to rouse, to startle it to a life of constant and eager observation. Every moment some form grows perfect in hand or face; some tone on the hills or the sea is choicer than the rest; some mood of passion or insight or intellectual excitement is irresistibly real and attractive to us, — for that moment only. Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end. A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to be seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to point, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy?

To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life. In a sense it might even be said that our failure is to form habits: for, after all, habit is relative to a stereotyped world, and meantime it is only the roughness of the eye that makes any two persons, things, situations, seem alike. While all melts under our feet, we may well grasp at any exquisite passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment, or any stirring of the senses, strange dyes, strange colours, and curious odours, or work of the artist's hands, or the face of one's friend. Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the very brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing of forces on their ways, is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening. With this sense of the splendour of our experience and of its awful brevity, gathering all we are into one desperate effort to see and touch, we shall hardly have time to make theories about the things we see and touch. What we have to do is to be for ever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions, never acquiescing in a facile orthodoxy of Comte, or of Hegel, or of our own.

From The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry by Walter Pater.

Weekend at Cafe Mochiko

A few weeks ago I spent the weekend working in a kitchen of what may be the best ramen shop in the country, which happens to be in Cincinnati, Ohio.

As part of the publicity for my cookbook, I solicited blurbs from a handful of ramen chefs. One of them was Erik Bentz, who, along with his wife Elaine Uykimpang Bentz, runs Cafe Mochiko, a bakery/coffee shop by day and a Japanese restaurant at night that’s received impressive accolades and glowing press coverage, mostly focused on Elaine’s expert pastry work.

After looking at the book and sending me a blurb, Erik invited me to visit and work the service for the cafe’s four-year anniversary. He thought it might be illuminating for me to see ramen being made in a professional kitchen. I haven’t ever worked in a professional kitchen; the closest I’ve gotten was the handful of nights I moonlighted as a dishwasher one summer in the Japanese alps. So I accepted; it would be an education.

Naively, I thought I knew what I was in for. By now, we’ve all seen it all before: the naïf enters a restaurant kitchen, learns a few things. They gain an appreciation for ingredient quality, learned skills, technique. They adopt kitchen jargon, kitchen discipline, rough kitchen manners. They reassess the craft and the craftsmen, which both take on a shine. They emerge, changed.

A little of that happened, of course. I cut up pork shoulder, folded wontons, sliced scallions, pried apart dried scallops and dried infant sardines with my fingers; for service, I washed and plated tsukemen, glazed the wontons I’d folded, added toppings to shoyu ramen. I did a modicum of real kitchen labor without embarrassing myself too much; I watched in wonder as the kitchen crew did their daily work; I said “behind” a lot. I was edified and impressed, and I left, in a sense, inspired.

Mostly, however, I left Cincinnati feeling a bit silly, because the ramen was so good, its quality so much higher than anything I’d expected, even though my expectations were quite high. I’ve spent the last couple weeks in a state of shock.

I’d met Erik briefly once before—not really face-to-face, if I recall it correctly. We were sort of introduced from across the counter separating the kitchen and the dining room at Rai Rai Ken, where Keizo Shimamoto held a popup swansong to commemorate the end of Ramen Shack; ramen nerds and ramen talent flocked to it from across the country. I’ve since followed Erik’s work on Instagram, and while it’s difficult to gauge the quality of ramen through a screen, anyone who makes ramen—even a tinkerer, a tourist, like me—can tell he has a defined style and sensibility, good technique. I’ve quizzed Keizo about Erik’s ramen in the past. “It’s probably one of the best ramen shops in the country,” he said.

I shouldn’t have been unprepared.

I arrived at about noon on Saturday, left early on Monday morning, and spent about 20 hours total in the kitchen. In that time, I ate six stellar bowls of ramen, each one far better than anything you can get around here in New York. And it wasn’t just that they were all delicious; the six bowls of ramen spanned a range of styles and contained (I think) five different kinds of noodles, and every one was distinct, beautifully made, delicious and interesting to eat. I would have been happily surprised if I’d encountered any one of those bowls in Japan.

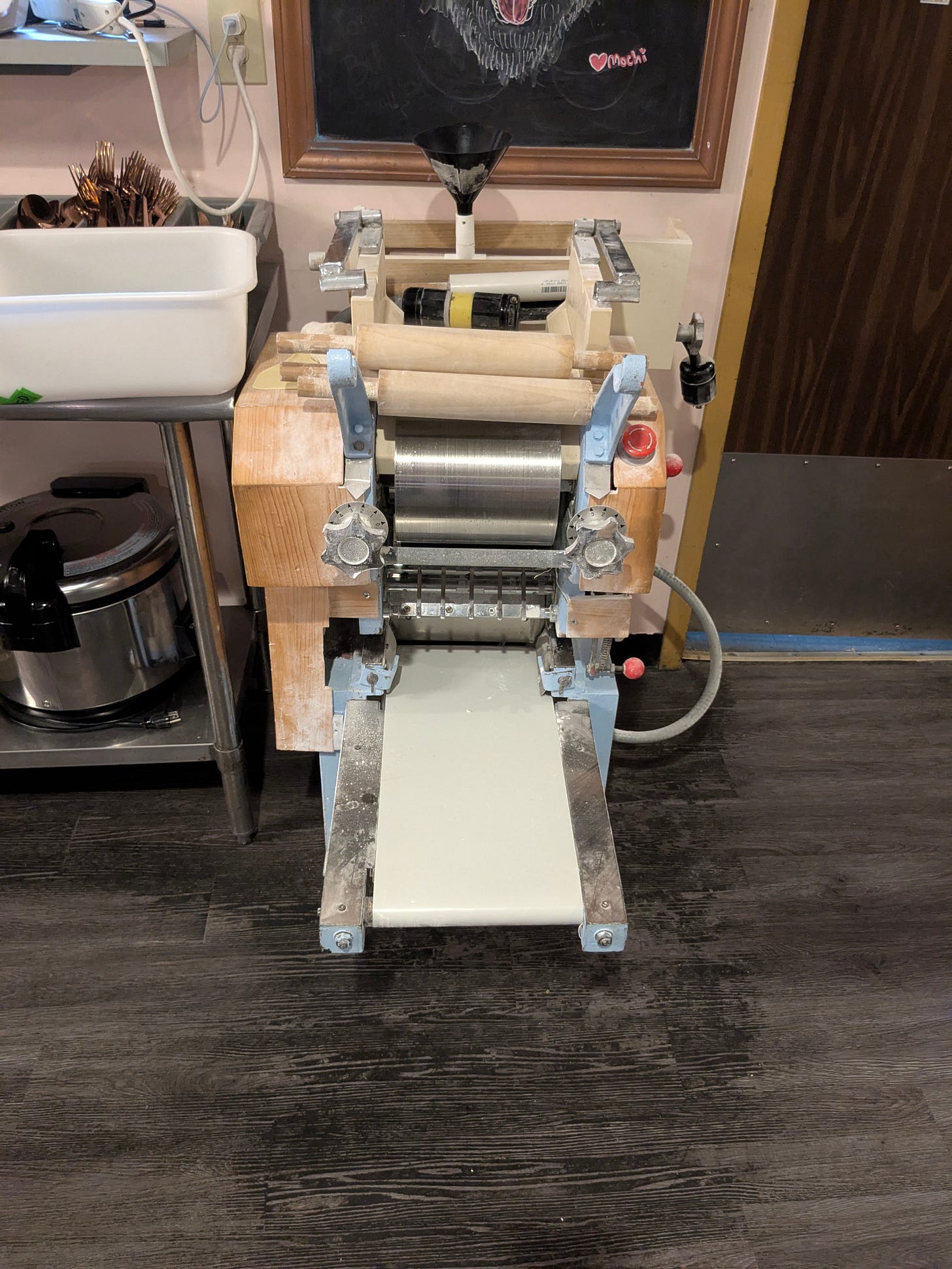

Years ago, when I wrote about Keizo’s Ramen Shack, part of what made the experience unique was his expansive range, his drive to create and serve a bunch of different kinds of ramen all the time, tailoring the noodles for each bowl. Erik clearly has that drive, just like a handful of ramen chefs with shops across the country with their own commercial noodle machines—Scott LaChappelle at Pickerel in Providence; Mike Satinover at Akahoshi Ramen in Chicago, to name just two, although there are a few more. (This trend deserves a longer, deeper, exploration of its own.)

But I still remember the thrill of discovery when I first ate Keizo’s ramen, sitting on a rickety stool in a cavernous warehouse space in Brooklyn, eating a bowl of shoyu ramen out of a plastic takeout container. It wasn’t just that it was tasty—it was that its flavors resonated deeply with what I understood ramen was supposed to taste like. It tasted like the ramen I loved to eat in Japan, a basic threshold of quality that most of, if not all, the ramen I’d had in America up until that point had failed to reach.

Shortly after I arrived at Mochiko, I experienced something similar. The kitchen was still turning over, the bakery operations wrapping up while prep for dinner service began, and Erik squeezed in the time to bang out two bowls of ramen, which I ate one after the other alone in the empty dining room.

The first was a “simple” shio ramen, beautifully irregular noodles swimming in a pellucid soup stained yellow by the chicken fat slicking the surface, adorned with nothing more than two twigs of seasoned bamboo shoots and finely sliced long onion. (Here I’ll apologize for all the photos, mostly to Erik, since they don’t do the elegance of the noodles and the refinement of the soups justice.) Shio ramen is not my preferred kind of ramen, as it seems to often lack a dimension of flavor that only soy sauce or miso can produce. But this shio tasted full.

Part of that was the noodles. Because they’d been pressed and squished before cooking (temomi, for the ramen heads), they possessed varying thicknesses and textures all along their lengths; because of the formula (and, I’d later discover, the addition of whole egg) they had a bouncy and slippery and lightly sulfurous quality that was a little unexpected. But the soup itself was incredible. Unlike a lot of otherwise good shio ramen I’ve had, where the salt itself seems to take over and in the process underlines areas of absence in the overall flavor profile, there was no emptiness at all. Its flavor—light, but clear—seemed to be everywhere all at once, as if I was sunk in a pool of it, breathless at the bottom, observing the disparate elements—scallop, kombu, onion, katsuobushi, chicken—announce themselves and fade away like the slow play of cloud shadows scudding across a pool’s surface, and every so often a bit of lemon zest would arrive, a surprise, a penny thrown for good luck glittering gemlike on tile.

I barely had enough time to deposit the empty bowl in the dish pit and mumble something about how it was amazing before Erik gave me the second bowl, a “simple” shoyu: straight, thinner noodles suspended in a caramel-colored broth, glistening with more of that chicken fat, a lone sheet of nori obscuring the menma and long onions. I am a “shoyu guy”; I make a lot of shoyu ramen; and I judge most ramen restaurants (sometimes unfairly) on the quality of their shoyu. And Erik’s is excellent, that same fullness the shio surprised me with, but richer, thanks to the very good and interesting soy sauce he uses. The first sip of the soup alone was enough to vault it near to the top of my mental list of the best ramen I’ve ever had.

I was—am—smitten. But beyond that, I was impressed. It is one thing for a ramen shop to make a single superlative bowl of noodles—shio, shoyu, miso, whatever style they decide is their focus; it is another thing entirely to produce two. Later that night, I got to try Erik’s Cincinnati chili ramen—a favorite of the non-ramen-nerd food writer crowd, and consequently suspect—and it wasn’t just better than it had any right to be; it was simply an excellent bowl of ramen. (Something magical happens at the bottom of the bowl when the dregs of the soup and the shredded cheddar and the bits of chili combine and emulsify into gloriously good goop.) (That’s three.) After service, the kitchen staff all sat down for the tonkotsu gyokai tsukemen we’d been serving all night, and it might as well have been the shop’s specialty—thick, long, slightly crinkly, and chewy noodles served with a thick, but not too viscous, emulsified pork soup spiked with dried fish. (That’s four.)

The next day was Mochiko’s anniversary, and Erik planned to serve two bowls of ramen: a shio tanmen with shrimp and a tokusei shoyu. “Tokusei” basically means “house special,” so it was a shoyu with a bunch of toppings: two kinds of chashu (medium-rare loin and braised shoulder), menma, blanched yu choy, and two wontons. It’s very hard to identify, let alone explain, the differences between two bowls of shoyu ramen, but, aside from the toppings (which were, to a piece, wonderfully prepared) this shoyu scanned bolder, with niboshi-spiked lard and a stronger soy sauce flavor than the one the day before. (That’s five.)

But I was most impressed by the shio tanmen—shio ramen with stir-fried vegetables on top. It had sort of been my idea; in the weeks before I’d arrived, Erik and I had spitballed ideas for a bowl that he’d make that was “inspired” by my cookbook. I noted that the shio tanmen in my book was inspired by the one I love at Hokuto, a mom-and-pop ramen spot that’s right around the corner from my grandmother’s house in Fukushima, and I sent him a post about it from my Instagram. Erik ran with it, and decided to add shrimp to the stir-fried vegetable topping—and, because he wanted to do wontons for the tokusei, decided to serve alongside a couple wontons tossed in a shrimp stock glaze.

It wasn’t the same as the one from Hokuto—how could it be, since Erik had never had that one—but he managed to capture its lardy, garlicky spirit perfectly. Nicely charred cabbage, tender-crisp bean sprouts, wilted wisps of garlic chives, and plump pieces of shrimp, all coated in some more of that shrimp stock glaze, floated on top of an aggressive shio soup. Where the first shio was restrained, this one was unapologetic, sweet from multiple kinds of shellfish in the stock, bumped up a little by chicken bouillon powder (Totole, the best bouillon powder!) in the stir-fry. And the noodles were relatively thick and chewy and very close in alkalinity and slipperiness to the hand-cut ones that swim in the soup at Hokuto.

One of the reasons the experience befuddles me is that I’ve had this theory that making good ramen—making anything, really—rests almost entirely on how much experience you’ve had eating it. If you haven’t eaten good versions of it, you have no idea what you’re shooting for in the first place; if you haven’t eaten a bunch of different good versions of it, you not only have no way of understanding how high the standards of excellence are, you have no context for understanding how far you are from achieving them.

People like Keizo, who have dedicated a significant amount of time and effort to eating thousands of bowls of ramen in Japan, naturally have an advantage; people like me, who grow up eating ramen of a quality that is much higher than the average quality of ramen in the US, also have a leg up. This is why the better ramen shops in the country are run by Japanese people, and why the average quality of ramen shops in Japan is so much higher than anywhere else. It isn’t some atavistic ability; it’s mostly exposure and experience. (The same, of course, could be said about pizza in New York or tacos in Mexico City.)

But Erik, who first visited Japan as an adult and has since visited just a handful of times, upends the theory. Before I went to Cincinnati, I could imagine a trained chef like Erik trying a baker’s dozen of great bowls of ramen in Japan and some of the best we have to offer in America and making something very tasty—that was, in fact, what I had expected. I did not think that he’d take that relatively limited experience and produce something spectacular—repeatedly, seemingly effortlessly.

Here I’ll address the hedge I made at the top: Is it the best ramen shop in America, or is it merely one of the best shops in the country? A month ago I might have said, yes, it’s certainly the best; the only shop that I’d eaten at that operated on both this level of quality and proficiency with a range of styles was Keizo’s, which no longer exists. I would’ve said, “I can’t imagine another American chef is making better ramen than Erik Bentz.”

The problem is this visit to Cincinnati left me humbled; my imagination, it appears, is shit. Having ogled Erik’s ramen for years online, fairly sure about its level of quality, I discovered I was—am—kind of a fool.

There are other promising ramen shops out there that seem to be in pursuit of the excellence Erik appears to be engaged in; I mentioned two above, but there are, at least, four more by my count. (Next noodsletter, I’ll talk about the ramen I ate at Pickerel in Rhode Island—I am not throwing shade at it by giving praise to Mochiko, you’ll see.) And there are many ramen restaurants across the country that I haven’t tried. I’m not even sure if I’m interested in the question, but to begin to answer it, I’d have to try them all at least once.

But is there any other ramen shop I’d like to eat at more than Mochiko, right now, anywhere in the United States? No.

And while I’d gladly eat anything Erik’s got to offer, I want to eat that first shio, the simple one, again—I’d like to eat it a couple times. From what I saw while working in his kitchen, I suspect it’ll be even better.

I could read your writing about ramen all day. Beautiful, Sho. You were born to eat and write about this.

I also love your Ramen writing.

I’d love to see your input on ramen shops at Southern California’s South Bay restaurants with a strong Japanese enclave that’s been there for generations (kind of a current reboot of Keizo’s GoRamen).